Future physicians receive training to address obesity and its complexities

Medical students learn to empower patients with sustainable strategies from VCU Health's innovative Medical Weight Loss Program.

March 21, 2025 Susan Wolver, M.D., and Edmond Wickham, M.D., co-lead a four-week elective rotation for fourth-year medical students in VCU Health’s Medical Weight Loss Program. (Arda Athman, VCU School of Medicine)

Susan Wolver, M.D., and Edmond Wickham, M.D., co-lead a four-week elective rotation for fourth-year medical students in VCU Health’s Medical Weight Loss Program. (Arda Athman, VCU School of Medicine)

By Laura Ingles

Susan Wolver, M.D., attended medical school in the 1980s. At the time, she said, the curriculum “didn’t include a single talk” on nutrition, obesity or weight management. So for years, when patients in her internal medicine clinic sought her help with weight loss, she gave them the same guidance she had always received: eat less, move more.

It wasn’t until she found herself struggling to lose her own perimenopausal extra pounds that she realized weight loss is more nuanced than exercising and eating in a calorie deficit.

“So, I found a new way,” she said.

Through her own extensive research and some trial and error, Wolver found that a system emphasizing “slow, sustainable change” helped her lose that extra weight. Realizing how beneficial this knowledge would be to her patients, Wolver began exploring how to scale it, earning a certification in obesity medicine and shadowing a leader in the internal medicine subspecialty at Duke University Hospital.

In May of 2013, she contacted a dozen patients who had expressed frustration with their weight and officially launched the Medical Weight Loss Program at VCU Health.

“We know that for many patients, simply eating less and moving more just doesn’t work,” said Wolver, clinic director of the program. “What does work is a truly multidisciplinary approach to getting to know the individual in front of you and figuring out why they struggle with weight.”

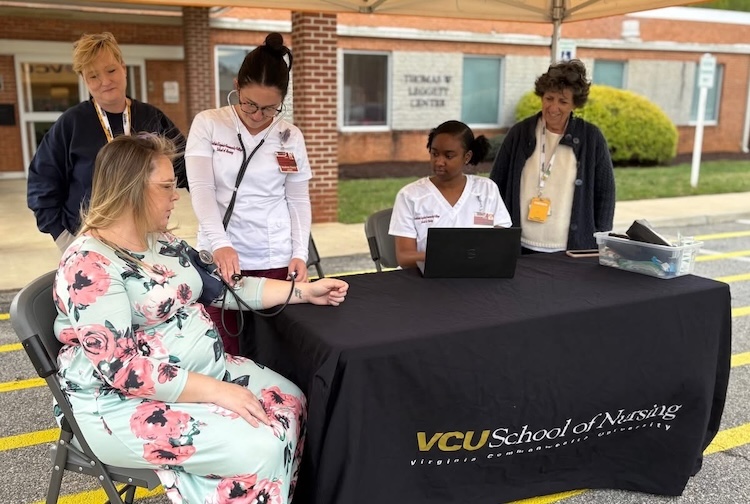

Nearly 12 years later, the program has grown to include a team of obesity medicine specialists, dietitians and behavioral health counselors, a months-long waitlist and a four-week rotation for medical students. Available to fourth-year students in Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Medicine, the subspecialty elective addresses a gap in medical education and prepares future physicians in any field to treat and support patients with obesity.

Finding the ‘why’

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of 2023, approximately 40.3% of adults in the U.S. — about 100 million people — have obesity, which is defined as having a body mass index of 30 or higher. Despite the prevalence of obesity and associated health risks, a 2024 report in the Advances with Nutrition medical journal found that “most medical schools fail to include the recommended minimum of 25 hours of nutrition training” set by the National Academy of Sciences.

Sriya Kolli, a VCU medical student who plans to pursue internal medicine, said a healthy diet was “not something we really dove into during our preclinical education.” She was eager to join the obesity medicine elective rotation last year, both to inform her future practice as a physician and to help her own family.

“In my culture, people comment on other people’s weight all the time, and I feel like it’s something you can never escape,” said Kolli, whose family is from India. She said her cousins have described their weight gain — and subsequent comments from grandparents and aunties — as isolating and embarrassing. “It has always been such an enigmatic, stigmatized topic, and I wanted to learn how to have these conversations with my patients and with my family.”

Edmond Wickham, M.D. FAAP, interim chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, co-leads the elective with Wolver. He said his patients with increased body weights often face bias and discrimination from a variety of sources, including health care providers, and that research data suggest that these experiences negatively affect health outcomes. He noted that patients with obesity may also receive unsolicited and misdirected advice and comments from family members and peers who, despite good intentions, perpetuate negative stigmas around obesity.

“People make assumptions about others based on their body size, and bullying is, unfortunately, a common element of many kids’ stories,” Wickham said. “Whenever I hear a story like that from a patient, I pause and say, ‘That’s not OK, and I’m sorry you experienced that.'"

One of Kolli’s first patients during her obesity medicine rotation was a young woman with a binge eating disorder. This patient was a couple of weeks into the weight loss program and openly shared about her childhood trauma and other experiences that triggered her emotional eating responses.

“I didn’t think about the way obesity can be an addiction, and the biological, social, and psychological reasons it can happen,” Kolli said. “I got a lot more insight into patients’ lives than I anticipated, which was really cool.”

This personal touch is by design. Wolver noted that everyone who joins the program has “an entirely different set of reasons” for being there, and it is their job as providers is to help identify those reasons and customize the weight loss approach accordingly. Taking a patient’s history involves a thorough mental health screening for depression, anxiety, stress and trauma, along with an exploration of environmental factors (e.g., their proximity to grocery stores, cooking skills, family situation and other social determinants of health).

Even though the training is only four weeks long, Kolli still got to see progress in her patients, such as improved self-esteem and changes in how they speak about themselves and their relationship to food. That knowledge stuck with her, too.

“This experience is going to help me be a better provider, especially if I go into primary care,” Kolli said. “And I want to advocate for more education, like didactic lessons in residency that focus on weight, because it’s such a prevalent issue in our society.”

Wolver said she can tell whether a student has truly understood what the clinic is about if, by the end of the four weeks, they are choosing their words more carefully when speaking to or about patients with obesity.

“Students are really changed after this rotation,” Wolver said. “It’s not just about learning a new discipline, but how they’ll speak with patients forever, and how they view that person they’re next to who may have a problem with obesity.”

Wickham, a VCU School of Medicine graduate who completed VCU’s combined internal medicine and pediatrics residency program and endocrinology fellowship in the early 2000s, noted that the elective is nearly always full. This, he said, speaks to the need for obesity medicine training across the continuum of undergraduate and graduate medical education.

“An understanding of how to approach and collaborate with patients with obesity in a way that is supportive, empowering and non-blaming, is probably the most important skill for somebody that’s treating obesity,” Wickham said. “That’s something we really highlight with our elective, and that our students can take away into their subsequent medical practice, regardless of where they’re going.”

A multidisciplinary approach to weight loss

In addition to the clinical education, the four weeks Kolli spent with patients in the weight loss program had a lasting personal impact — it changed the way she approaches her own nutrition.

“The way I eat now is the way Wolver recommends to patients, which is a very common experience for students who rotate with her,” Kolli said. “I’ve also inspired people in my life to do the same. As you learn, you pass it along to the people around you and have this ripple effect.”

Wolver, Wickham, and the team work with adult and pediatric patients to create a weight loss plan that prioritizes “direction over speed and consistency over intensity.” This comprehensive method addresses lifestyle factors that can impact weight gain, like nutrition and exercise, but also sleep, stress and social connections. The team also works closely with the adult and adolescent bariatric surgery providers at VCU Health and Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU (CHoR), providing what Wolver described as a “seamless experience for patients who start at one spoke or the other.”

Patients have access to a private Facebook group for support and recipe sharing, and educational sessions cover topics like navigating grocery stores, interpreting nutrition labels and meal prepping. On the pediatric side, patients receive comprehensive care and family-centric education through the Weight Management and Healthy Lifestyles Center at CHoR, the only center of its kind in the region.

The nutrition plans are built around a low-carbohydrate approach, with the level of carb reduction based on “what the patient wants to do,” Wolver said. For example, Kolli recalled a patient who was unwilling to eliminate cereal from their diet, so she helped them find a lower-carb, higher-protein cereal that they still enjoyed.

“The program teaches that there are no enemy foods, and how to be a little more conscious of what you’re putting into your body,” Kolli said. “It’s all about finding alternatives when possible, and when not possible, just eating in moderation.”

People come to the medical weight loss program from all walks of life, including single parents who have to shop at convenience stores and truck drivers who eat out for nearly every meal. Provided a patient is ready and willing to adjust their habits, Wolver and Wickham are confident the program can help them.

"The only people we can’t help are the ones who stop showing up,” Wolver said.

Weight Loss Drugs 101: Benefits and risks you need to know before picking up a prescription